The History of Phenolics In Healthcare Disinfection

Phenolic compounds have played a defining role in the history of medical disinfection, shaping modern practices in infection control and hospital hygiene. Their story is one of discovery, innovation, and ongoing evolution as scientists and healthcare professionals sought better ways to prevent the spread of disease.

What Are Phenolics?

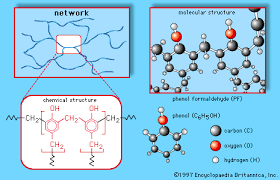

Phenolics are a broad group of chemicals characterized by a hydroxyl group attached to an aromatic ring. These compounds occur naturally in plants and can also be synthesized from sources like coal tar. They possess strong antimicrobial properties, making them effective against a wide range of bacteria, fungi, and some viruses. Over time, their chemistry and applications have been refined to produce even more effective and safer disinfectants.

Early Discovery and Chemical Innovation

The use of phenolic compounds dates back to the early 19th century, when coal tar was explored for various medical and industrial uses. Coal tar itself was found to have antiseptic properties, and by the mid-1800s, phenol (also known as carbolic acid) was isolated as a pure compound. This paved the way for its adoption in medical settings as an agent capable of killing pathogens on surfaces and instruments.

Scientists soon discovered that the structure of phenolic compounds played a critical role in their germicidal activity. This realization led to the development of a variety of phenolic derivatives, many of which became foundational ingredients in antiseptics and disinfectants.

Joseph Lister and the Dawn of Surgical Antisepsis

The turning point for phenolics in healthcare came in the 1860s. British surgeon Joseph Lister, inspired by new understandings of germ theory, began using phenol to sterilize surgical instruments and cleanse wounds. Lister’s use of carbolic acid dramatically reduced surgical infections and set a new standard for sterile technique in the operating room.

His methods quickly spread worldwide, ushering in the era of antiseptic surgery. By demonstrating that infections could be prevented rather than simply treated after the fact, Lister’s work transformed both surgery and the broader field of hospital hygiene.

Widespread Adoption and Use in Healthcare

With Lister’s success, phenol and other phenolic compounds became some of the earliest and most widely used disinfectants in hospitals. They were used to clean wounds, sterilize instruments, and disinfect surfaces. Their popularity continued for much of the 20th century, not only in professional healthcare settings but also in consumer products and household cleaning agents.

Phenolic derivatives, like cresols and other specialized compounds, were developed to enhance effectiveness and reduce toxicity. This allowed for an even greater range of applications, including surface disinfectants, institutional cleaning, and preservation of industrial materials.

Despite their effectiveness, phenolic compounds are not without drawbacks. Phenol itself can be harsh on skin and mucous membranes, causing burns or irritation with prolonged exposure. Over time, concerns about toxicity and environmental persistence led to a gradual decline in the use of pure phenol in healthcare.

In the 1970s, hospitals in the United States experienced outbreaks of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (jaundice) among newborns, which was traced to the use of phenolic disinfectant detergents in nurseries and neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Phenolic compounds, commonly used as disinfectants, were applied in excessive concentrations to clean bassinets, incubators, and mattresses. This led to a significant increase in cases of jaundice severe enough to require exchange transfusions in affected infants.

Phenolic compounds can be absorbed through the skin or inhaled, especially in newborns whose skin and metabolic systems are immature. Excessive exposure in these hospital outbreaks led to increased bilirubin levels, resulting in jaundice. In severe cases, this can cause neurological damage if not promptly treated.

A prospective study later compared the incidence of neonatal jaundice when phenolic versus non-phenolic disinfectants were used, further supporting the association between phenolic exposure and higher rates of jaundice in newborns

Key Incidents

• New Jersey, 1972: Nine neonates required exchange transfusions for idiopathic hyperbilirubinemia over a short period. The spike in cases coincided with increased use of a phenolic disinfectant detergent by nursing staff. The problem resolved after discontinuing the phenolic compound.

• Wyoming, 1975: A similar outbreak occurred, with 10 out of 54 newborns developing idiopathic hyperbilirubinemia. Excessive concentrations of the same phenolic disinfectant, coupled with poor nursery ventilation, were implicated. Once the disinfectant was withdrawn and ventilation improved, the epidemic ceased.

The phenolic problem in hospitals refers primarily to outbreaks of severe neonatal jaundice linked to the excessive use of phenolic disinfectants in nurseries and NICUs. These incidents led to changes in hospital cleaning protocols and increased awareness of the risks of chemical exposures in vulnerable newborn populations. Ongoing research continues to monitor phenol exposure in infants to prevent similar health risks in the future.

Limitations and Modern Perspectives

Over time, concerns about toxicity and environmental persistence led to a gradual decline in the use of pure phenol in healthcare.

Advancements in chemistry and microbiology have ushered in new classes of disinfectants, including quaternary ammonium compounds and bleach, which are less hazardous and equally effective. Today, while phenolic-based products are still found in some institutional disinfectants and preservatives, their use has been largely superseded by safer alternatives.

Legacy and Continuing Impact

The legacy of phenolics in healthcare disinfection is profound. They demonstrated the value of chemical disinfection in controlling infection and paved the way for modern antiseptic and sterilization practices. Even though their direct use has diminished, many current disinfectants are based on the chemistry and efficacy principles established by early phenolic compounds.

pdihc.com

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

cloroxpro.com

ami-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

basicmedicalkey.com