More Than a Menace: The Secret Histories of the World’s Toughest Germs

What is the first thing you notice when you enter a hotel or hospital room? I believe, most people register a simple impression: it is either clean and smells fresh, or it isn’t. This feeling of cleanliness gives us a sense of safety and comfort, a sign that professionals have worked tirelessly to prepare the space just for us. But what if that sterile scent masks an invisible world with a dramatic history of its own?

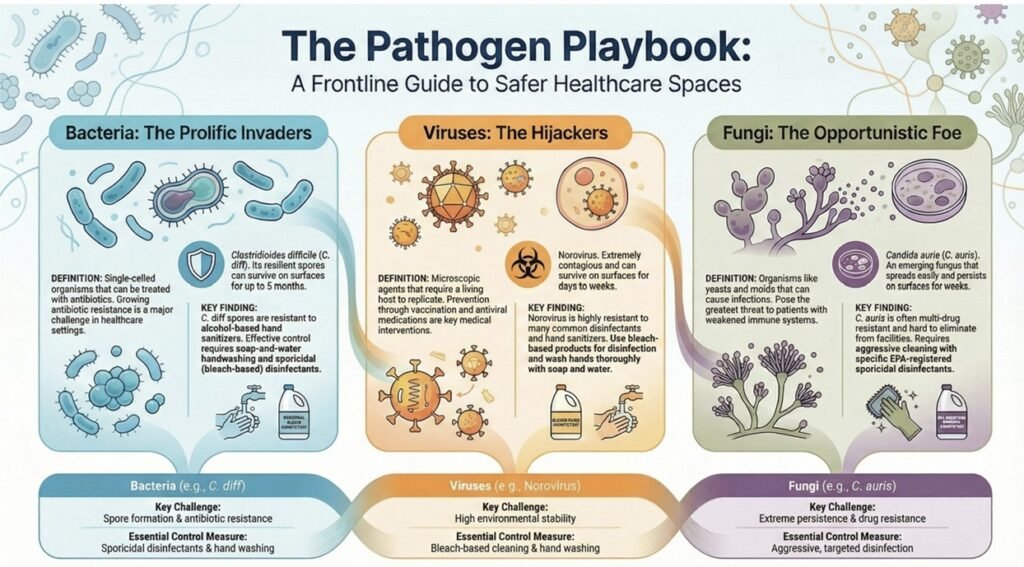

Behind that spotless surface lies a complex, hidden world. Environmental service professionals are on the front lines of a daily battle against microorganisms, many of which are far more than just generic “germs.” These pathogens have unique identities, surprising origins, and counter-intuitive histories that read like scientific detective stories. Here are a few of the most fascinating backstories hiding in the microscopic world from my upcoming Pathogen Playbook.

1. Discovery Can Be Accidental, and Naming Can Be Mythological

In 1928, scientist Alexander Fleming returned from holiday to find a forgotten petri dish held a world-changing secret: a halo of death where a stray mold spore had landed, dissolving the deadly Staphylococcus aureus bacteria around it. In that moment of chance, the age of antibiotics was born. Yet even then, Fleming presciently warned that bacteria could learn to resist his new wonder drug. His warning was a prophecy, and today’s environmental service professionals are on the front lines of the war he foresaw, fighting organisms that have long since learned to outsmart our best medicines.

Other discoveries reveal a flair for the dramatic. In 1819, Italian pharmacist Bartholomeo Bizio was confronted with polenta that appeared to be bleeding. He identified the cause as a bacterium he named Serratia marcescens. Initially, it was considered so harmless that its distinctive red pigment made it a popular biological marker in experiments. Decades later, a German pathologist named Gustav Hauser observed another bacterium’s astonishing behavior. He saw not just a microorganism, but a living tide that spread across the culture plate in a mesmerizing, coordinated wave—a performance so uncanny he reached not for a scientific manual, but for ancient Greek myth, naming it Proteus mirabilis after the shape-shifting sea god who could alter his form to escape his captors.

2. What’s in a Name? Sometimes, a Misconception.

While some pathogen names are poetic, others can be outright misleading. Mpox, for instance, was first identified in research monkeys in 1958, which is how it got its name. However, scientists now believe its natural hosts in the wild are not monkeys at all, but various species of African rodents.

The story of the genus Salmonella is a classic case of mistaken identity and misplaced credit. In 1885, Theobald Smith, an assistant to the American veterinary pathologist Daniel Elmer Salmon, isolated a new bacterium from sick pigs. Despite Smith doing the brilliant work, the organism was named after his boss. To add another layer of irony, the bacterium they found turned out not to be the cause of the hog cholera they were investigating—that was a virus. Another misnomer is the Pseudorabies virus. Despite a name that suggests a connection to the infamous rabies virus, it is not related. It is a type of suid herpesvirus, getting its name from the rabies-like symptoms it can cause in animals.

3. The Unseen Enemy is Incredibly Resilient.

The incredible resilience of certain pathogens makes the work of environmental services both critical and immensely challenging. The spores of Clostridioides difficile, for example, are extreme survivalists that can remain viable on surfaces for up to five months. They are also notoriously resistant to common alcohol-based hand sanitizers, meaning that only the diligent application of soap, water, and sporicidal disinfectants can break the chain of infection.

Some organisms thrive where they are least expected. Burkholderia cepacia, first discovered on rotting onion roots, is so persistent it has been found thriving even in antiseptics like betadine—a substance designed specifically to kill germs. A more modern threat, Candida auris, underscores the ongoing battle. First identified in a patient’s ear in Japan in 2009, this fungus is a healthcare nightmare because it spreads easily, persists on surfaces for extended periods, and is often resistant to multiple classes of antifungal drugs. These organisms don’t just exist; they endure. Their tenacity is a constant reminder of the vigilance required to maintain a safe healthcare environment.

4. There’s a Long, Slow Fuse Between Finding a Germ and Knowing What It Does.

The gap between discovering a new microorganism and understanding its impact can be dangerously long. For 43 years, a devastating hospital-acquired infection spread unchecked because its true cause remained a mystery. Clostridioides difficile was first identified in 1935, but its role in causing antibiotic-associated diarrhea was not established until 1978. This gap underscores how EVS teams are not just cleaning rooms; they are breaking chains of infection that science itself was once slow to understand.

A more recent drama unfolded with Legionella pneumophila. This bacterium was only identified after a deadly and mysterious pneumonia outbreak at a 1976 American Legion convention in Philadelphia. The disease was named “Legionnaires’ disease” after its first victims. After the culprit was found, however, retrospective analysis of previous unsolved outbreaks identified cases dating as far back as 1957. These stories show that scientific understanding is a process, not an event, and the journey from isolating an organism to containing it often has life-altering consequences.

The invisible world of pathogens is far from a simple list of faceless menaces. It is filled with fascinating stories of accidental discovery, mythological naming, extreme resilience, and long-delayed understanding. From a contaminated petri dish to a discolored serving of polenta, the history of these organisms reveals as much about human curiosity and perseverance as it does about the microbes themselves.

This knowledge reinforces the importance of what professionals like me call a “PMA – Positive Mental Attitude.” The fight for a clean, safe environment is a fight against organisms with incredible, complex backstories. It requires not just the right tools and techniques, but a vigilant, proactive mindset.

Knowing the incredible backstories of these organisms, how might it change our perspective on the importance of a positive, vigilant attitude toward cleanliness in our daily lives?